A multidisciplinary Design Day team designed an AI-powered chatbot to answer cancer patients’ questions accurately and empathetically.

By Jaimie Patterson

Though the rise of telehealth has made it easier for patients to access medical care, many still struggle to get timely answers and information from their physicians, especially when dealing with potentially life-threatening diseases like cancer.

That’s why a team of Johns Hopkins undergraduate students is developing an empathetic AI-powered chatbot to provide cancer patients and their families with instant, easy access to accurate medical information.

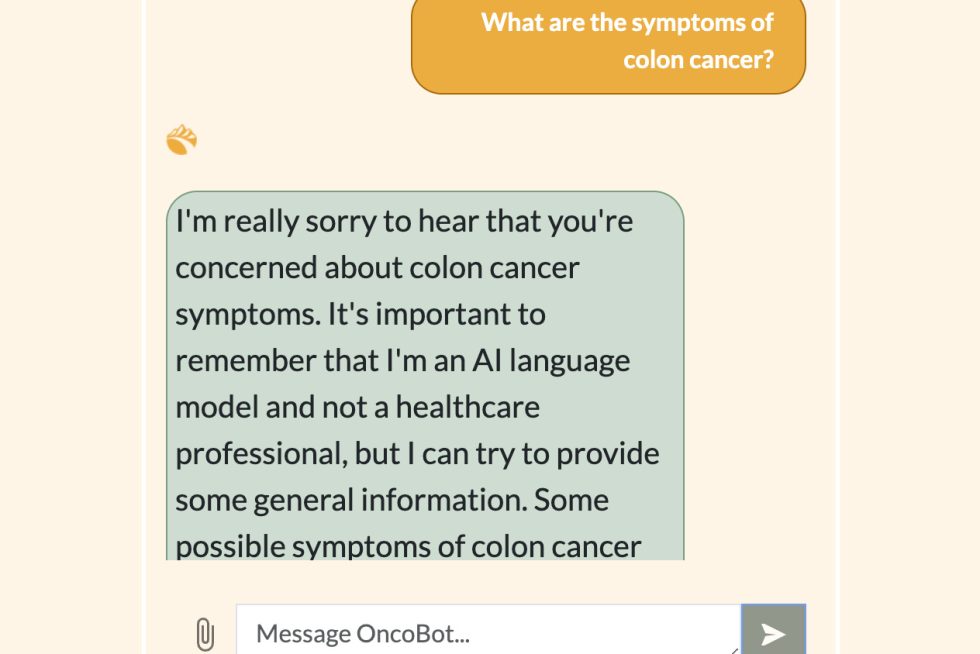

Their chatbot is based on OpenAI’s GPT model—which powers the famous ChatGPT—but with key differences: Not only has it been trained exclusively on credible, trusted sources of medical information but it is also designed to express sympathy and care. The team will present its finished model at the Whiting School of Engineering’s Design Day on May 1, where visitors can give the bot a trial run.

This project is the culmination of the Center for Leadership Education’s Multidisciplinary Engineering Design course, in which students from different engineering disciplines team up with industry sponsors to tackle real-world problems.

The team—comprising computer science students Ujvala Pradeep and Dee Velazquez; biomedical engineering student Resham Talwar; and chemical and biomolecular engineering student Himanshi Sharma—partnered with Utah-based Shoreline Health to enhance its patient education platform by creating the chatbot.

The project’s wide reach and possible impact are what originally piqued the students’ interest.

“It’s a huge amount of people that we can potentially impact,” said Sharma.

She and her teammates were additionally motivated when they discovered through preliminary research that a single doctor is often responsible for an average of 70 cancer patients.

“We wanted to minimize the load on these doctors with this project,” Sharma said. “If patients or their family members have a question, they can immediately learn the answer using our chatbot—rather than having to go through the whole process of getting an appointment and then finally speaking to their health care provider much later.”

Why not just suggest patients use ChatGPT? The team was concerned about the general-purpose chatbot’s bedside manner (or lack thereof), as well as its tendency to hallucinate, or simply make up false information.

“Our chatbot is more empathetic in the sense that the language it uses is more catered towards cancer and cancer patients. We’ve also trained it specifically on trusted, accurate cancer information to prevent it from hallucinating like ChatGPT,” said Sharma.

Their bot not only converses with patients, but also has a feature that allows users to upload research papers or medical reports and receive a near-instant—and accurate—summary of the work without having to wade through the challenging technical or clinical jargon themselves.

The students worked closely with real stakeholders throughout the design and testing of their chatbot. For instance, to gain valuable insights into the clinical side of the project, they met with William Nelson, the director of the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, and social workers with high caseloads of cancer patients. Currently, they are conducting user testing with cancer patients and survivors, their families, and those who have lost family members to cancer.

“This work has a real impact on human beings,” Sharma said. “I also would not have imagined myself meeting engineers from different disciplines if this project hadn’t happened; it’s just really cool to see everybody’s skills come together and then make something so interesting and so wonderful. It is very gratifying to have worked on a project like this.”